Sir Baptist Hicks

Mary Fielding

Baptist Hicks was a wealthy silk mercer who supplied the Court and made loans to many of the nobility including King James I. He made many benefactions to Campden and elsewhere.

Early Life

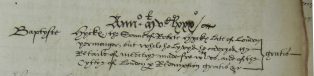

Baptist Hicks (or Hickes) was born in either late 1550 or early 1551, the youngest of six sons born to Robert and Juliana Hicks, only three of whom reached adulthood. Although his baptism is not recorded in the Parish Records for St Pancras, Soper Lane (the church burned down during the Fire of London in 1666 and many records were lost), three of his siblings were registered there and his father’s shop was nearby at the sign of the White Bear, so it is likely that he was also baptised at the parish church.

His father was a freeman of the Ironmongers’ Company, but actually traded as a silk mercer. In 1557, when Baptist was only 6, Robert died and his mother soon married again, a friend of her late husband, Anthony Penne. The three surviving brothers, Michael (eight years his senior), Clement and Baptist, attended St Paul’s School, close to where they lived. In due course, Baptist followed his brother Michael to Trinity College, Cambridge and the Inns of Court.

Michael entered the service of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, became his secretary and a friend of Robert Cecil; little is known about Clement apart from the fact that he lived in Chester and was some kind of Customs official; Baptist carried on as a mercer, probably taking over from his mother, who died in 1592, when he took over sole control of the business.

In 1584 Hicks married Elizabeth May, whose father, Richard, was a goldsmith. Although Baptist and Elizabeth had several sons, none survived beyond infancy. Their two daughters, Julian(a) and Mary married well with the benefit of huge dowries.

Mercer to the Court of Queen Elizabeth

Hicks became a Freeman of the Mercers’ Company in 1577 and was admitted to the Livery of the Mercers’ Company in 1686. During the 1580s and 90s he was moving up the City hierarchies and making contacts at Court, probably using the influence of brother Michael who was Secretary to Lord Burghley and Sir Robert Cecil, later Earl of Salisbury. By 1596 he was appointed Mercer to Queen Elizabeth and State Papers record the purchase of:

…Silks, Satins, Velvets and Taffetas, sold by Baptist Hicks, Merchant, to Sir Thomas Wilkes, on his going to Florence.

Total £68 3s. 2d.

[Wilkes was a diplomat employed on important embassies to Europe.]

The Sunday Times “Richest of the Rich: 250 wealthiest people in Britain since 1066” lists Baptist Hicks as the 2nd wealthiest man in England during his lifetime, worth the equivalent of £9.2 billion today.

Moneylender to James I

When James VI of Scotland ascended to the English throne in 1603 he brought his impoverished Scottish Court with him. Suddenly there was an urgent need for luxurious clothes and Hicks was there to supply the goods, extending considerable credit to his noble customers. For example in 1607 a warrant was issued to repay to Sir Baptist Hicks £12,000 with interest, part of a sum of £24,000, due from the Great Wardrobe and advanced to meet the King’s urgent needs. He also received lucrative concessions as an agent for the purchase and resale of royal lands.

James I knighted Hicks in 1603 and in 1620 he was created a baronet. He was MP for Tavistock in the parliament of 1621 and for Tewkesbury in the parliaments of 1624, 1625, 1626 and 1628. In 1628 he was elevated to the peerage as Baron Hicks of Ilmington, Warwickshire and Viscount Campden of Campden, Gloucestershire.

Baptist Hicks died in London in 1629 and is buried in Campden Church in this impressive marble monument by Nicholas Stone. As he had no direct male heirs, his son-in-law Edward Noel inherited his titles by a special remainder.

Public Benefactor

Sir Baptist Hicks, first Viscount Campden, made many benefactions to Campden including the Almshouses, the Market Hall and gifts to the Church which included the pulpit and the lectern.

The water-supply to his new manor house by the church and to the almshouses came from springs on Westington Hill and the tiny but elegant Conduit House is still to be seen.

Campden House

Sir Baptist Hicks’ new manor house, next to the church in Chipping Campden, was built in 1612 at a cost of £44,000 in the very latest style and with superb gardens, including a canal, water gardens, terraces and what is likely to have been a formal parterre, possibly with a central fountain.

Towards the end of the Civil War, in 1645, it was burned to the ground by order of the Royalist commander, Prince Rupert, in order to prevent it falling into the hands of the Parliamentary forces. The Gatehouse and two Banqueting Houses or pavilions remain together with some ruins of the house.

It is said that Lady Juliana Noel, Sir Baptist’s heir and widow of Edward Noel, second Viscount Campden, lived afterwards in the converted stables, now called the Court House, in Calf Lane.

For his town house, Hicks built a large mansion in Kensington, also called Campden House as well as a Sessions House for the Middlesex Magistrates which was called Hicks Hall in his honour. He acquired land and interest all over the country and left bequests worth around £10,000 in his will.

What did Campden House look like?

Little remains of Campden House and although there are prints showing what it looked like, none of these are contemporary. CCHS volunteers have carried out research over the past four years to try to reconstruct what the house and gardens might have looked like and CCHS has now published a book on the research findings. Go to the Campden House section to find out more.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page